Welcome back! I hope everyone (who celebrates) had a lovely Christmas!

Let’s get back to morphology!

Today, we’re not really doing historical linguistics, because, today, we’re looking at Modern English morphology.

Although Modern English is usually further divided into Early Modern English and Late Modern English and, by some, also into Present-Day English, we’ll do a general overview of this entire period – which stretches from 1500 to present day.

Why?

Well, because, honestly, English morphology really hasn’t changed all that much since Middle English (that is not to say that it hasn’t changed at all, just that it hasn’t changed so much that it would add to your knowledge to divide it into its “typical” divisions).

Up to this point, we’ve mostly focused on inflectional morphology.

Inflectional morphology refers to something that is added to a word for grammatical reasons – like case, gender, number, etc.

In this, English really hasn’t changed all that much. Like in Middle English, Present-Day English has three cases: nominative, accusative, and genitive. In any other word than a pronoun, the genitive is expressed by the apostrophe (as in “My dog‘s toy“), while in pronouns, we see a bit more of a difference:

| Nominative | Accusative | Genitive |

|---|---|---|

| I | Me | Mine |

| You | You | Yours |

| He | Him | His |

| She | Her | Hers |

| It | It | Its |

| We | Us | Ours |

| They | Them | Theirs |

| Who | Whom | Whose |

This is not really all that different from Middle English.

In Middle English (as we talked about last week), the case system underwent a weakening and lost the distinctive dative case by the early Middle English period. And since then, this is pretty much the system that has been used.

Modern English has no real grammatical gender system left – that is, it has a system that is mostly based on natural gender. What that means is that it makes no difference to an English speaker whether a word is technically a masculine, feminine or neuter because there is no distinction between the forms (or their modifiers) anyway. Even dictionaries in English (like Merriam-Webster) do not attribute a gender to an English word.

Instead, the word, if necessary, coincides with the subject’s natural gender. That is, if you’re talking about a woman, you’ll say she, while, if you’re talking about a man, you’ll say he.

This is really not all that different from Middle English either.

Grammatical gender started to disappear from English during the Middle English period and by the late 14th century, it is pretty much gone (at least in London English). So, not all that different.

Last: technically, we have eight inflectional morphemes in modern English:

| Morpheme | Function | Attaches to | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| 's | Genitive (possessive) | Nouns | The child's book |

| (e)s | Plural | Nouns | The books The wishes |

| (e)d | Past tense | Verbs | Baked (from bake) Played (from play) |

| -ing | Present participle | Verbs | I'm thinking |

| -en (also expressed by -ed, -d, -t, -n) | Past participle | Verbs | The boy taken to the hospital is getting better |

| -s | Third person singular | Verbs | The girl eats |

| -er | Comparative | Adjectives | He is smarter than most boys his age |

| -est | Superlative | Adjectives | She is the smartest girl in our class |

Though we might also want to add -en as a possible way to show plural (i.e. oxen, children). Again, this is not very different from what we find in Middle English.

However, there is another form of morphology:

derivational morphology.

We haven’t really talked about derivational morphology (which is actually rather interesting since I’ve spent a good amount of time trying to account for a specific derivational morpheme).

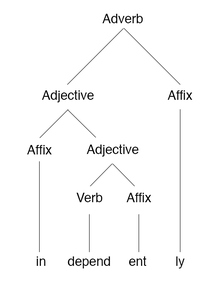

Anyway, morphological derivation is the process by which you create a new word by taking an existing word and adding a prefix or a suffix to it. (There are a number of other affixes, such as infix and circumfix, but they are less commonly used.)

Basically, you take a word, like child. Then you add a suffix to your word; let’s add -hood – and, suddenly, you got childhood! (-hood and its sister suffix –head just happens to be the suffixes I’ve spent a loooong time looking into).

I haven’t really focused on this but derivational morphology has been an active part of English morphology since Old English, and thus, we find cildhad (childhood) in Old English.

And there you have it, a brief overview of modern English morphology!

As you can see, in this very brief overview, there isn’t all that much that has changed from the Middle English period. That will soon change as we will, next week, start having a look at the development of English phonology! Check back then!

.

References

For this post, I’ve had a look at: