Hello there, faithful followers!

As you may have noticed, we have recently been running a bit of a series, called ‘Lies your English teacher told you’. Our ‘lies’ have included the prescriptive ideas such as (1) you should never split an infinitive; (2) you shouldn’t end a sentence with a preposition; and (3) two double negatives becomes a positive (in English). We’ve also taken a look at the ‘lies’ told to those taught English as a second, or foreign, language.

Now, dear friends, we have reached the conclusion of this little series and we will end it with a bang! It’s time, or rather overdue, that the truth behind these little stories be unveiled… Today, we will therefore unveil the original ‘villain’, if you will (though, of course, none of them were really villainous, just very determined) and tell you the truth of who told the very first lie.

Starting off, let’s say a few words about a man that might often be recognized as the first source of (most) of the grammar-lies told by your English teachers: Robert Lowth, a bishop of the Church of England and an Oxford professor of Poetry.

Bishop Robert Lowth

Lowth is more commonly known as the illustrious author of the extremely influential A Short Introduction to English Grammar, published in 1762. The traditional story goes that Lowth, prompted by the absence of a simple grammar textbook to the English language, set out to remedy the situation by creating a grammar handbook which “established him as the first of a long line of usage commentators who judge the English language in addition to describing it”, according to Wikipedia. As a result, Lowth became the virtual poster-boy (poster-man?) for the rise of prescriptivism and a fascinating amount of prescriptivist ‘rules’ are attributed to Lowth’s writ – including the ‘lies’ mentioned in today’s post. The image of Lowth as a stern bishop with strict ideas about the use of the English language and its grammar may, however, not be well-deserved. So let’s take a look at three ‘rules’ and see who told the first lie.

Let’s start with: you should never split an infinitive. While often attributed to Lowth, this particular ‘rule’ doesn’t gain prominence until nearly 41 years later, in 1803 when John Comly, in his English Grammar Made Easy to the Teacher and Pupil, notes:

“An adverb should not be placed between a verb of the infinitive mood and the preposition to which governs it; as Patiently to wait — not To patiently wait.”1

A large number of authorities agreed with Comly and, in 1864, Henry Alford popularized the ‘rule’ (although Alford never stated it as such). Though a good number of other authorities, among them Goold Brown, Otto Jespersen, and H.W. Fowler and F. G. Fowler, disagreed with the rule, it was common-place by 1907 when the Fowler brothers note:

“The ‘split’ infinitive has taken such hold upon the consciences of journalists that, instead of warning the novice against splitting his infinitives, we must warn him against the curious superstition that the splitting or not splitting makes the difference between a good and a bad writer.” 2

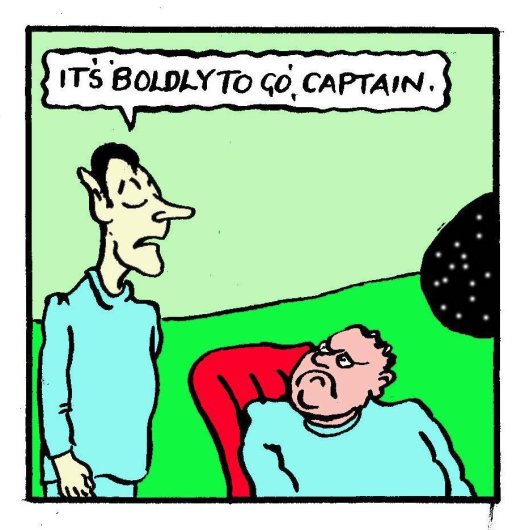

Of course, to split an infinitive is quite common in English today; most famously in Star Trek, of course, and we doubt that most English-speakers would hesitate to boldly go against this 19th century prescriptivist rule.

Now, let’s deal with out second ‘rule’: don’t end a sentence with a preposition. This neat little idea comes from a rather fanatic conviction that English syntax (sentence structure) should conform to that of Latin syntax, where the ‘problem’ of ending a sentence with a preposition is a lot less likely to arise due to the morphological complexity of the Latin language. But, of course, English is not Latin.

Still, in 1672, dramatist John Dryden decided to criticize Ben Jonson for placing a preposition at the end of a sentence rather than before the noun/pronoun to which it belonged (see what we did there? We could have said: … the noun/pronoun which it belonged to, but the rule is way too ingrained and we automatically changed it to a style that cannot be deemed anything but overly formal for a blog). Anyway.

The idea stuck and Lowth’s grammar enforced it. Despite his added note that the fanaticism about Latin was an issue in English, the rule hung around and the ‘lie’, while certainly not as strictly enforced as it used to be, is still alive and well (but not(!) possible to attribute to Lowth).

Last: two double negatives becomes a positive (in English). First: no, they don’t. Or at least not necessarily. In the history of English, multiple negators in one sentence or clause were common and, no, they do not indicate a positive. Instead, they often emphasize the negative factor, an effect commonly called emphatic negation or negative concord, and the idea that multiple negators did anything but form emphatic negation didn’t show up until 1762. Recognise the year? Yes, indeed, this particular rule was first observed by Robert Lowth in his grammar book, in which it is stated (as noted in the Oxford Dictionaries Blog):

“Two Negatives in English destroy one another, or are equivalent to an Affirmative.”

So, indeed, this one rule out of three could be attributed to Lowth. However, it is worth noting that Lowth’s original intention with his handbook was not to prescribe rules to the English language: it was to provide his son, who was about to start school, with an easy, accessible aid to his study.

So, why have we been going on and on about Lowth in this post? Well, first, because we feel it is rather unfair to judge Lowth as the poster-boy for prescriptivism when his intentions were nowhere close to regulating the English language, but, more importantly, to tell you, our faithful readers, that history has a tendency to change during the course of time. Someone whose intentions were something completely different can, 250 years later, become a ‘villain’; a ‘rule’ that is firmly in place today may not have been there 50 years ago (and yes, indeed, sometimes language does change that fast); and last, any study of historical matter, be it within history; archeology; anthropology or historical linguistics, must take this into account. We must be aware, and practice that awareness, onto all our studies, readings and conclusions, because a lie told by those who we reckon should know the truth might be well-meaning but, in the end, it is still a lie.

Sources and references

Credits to Wikipedia for the picture of Lowth; find it right here

1 This quote is actually taken from Comly’s 1811 book A New Spelling Book, page 192, which you can find here. When it comes to the 1803 edition, we have trusted Merriam-Websters usage notes, which you can find here.

2 We’ve used The King’s English, second edition, to confirm this quote, which occurs also on Wikipedia. The book is published in 1908 and this particular quote is found on page 319, or, right here.

In regards to ending a sentence with a preposition, our source is the Oxford Dictionaries Blog on the topic, found here.

Regarding the double negative becoming positive, our source remains the Oxford Dictionaries Blog on that particular topic, found here.

Or rather, “To go boldly”1

Or rather, “To go boldly”1