Hello, it’s me, Lisa, again. I just couldn’t stay away! This week, I have been given the challenging task of outlining the subfields of linguistics1. The most common responses I get when I tell people I study linguistics are variations of “What is that?” and “What can you do with that?”. This leads me to explain extremely broadly what linguistics is (eh, er, uhm, the science of languages? Like, how they work and where they come from…. But I don’t actually learn a language! I just study them. One language or lots of them. Sort of.), and then I describe various professions you can have from studying linguistics. What all of those professions have in common is that I can do none of them, since they are related to subfields of linguistics that I haven’t specialised in (looking at you forensic and applied linguistics). My own specialties, historical linguistics and syntax, lead to nothing but long days in the library and crippling student debt, but let’s not dwell on that.

Linguistics is a minefield of subdisciplines. To set the scene, look at this very confusing mind-map I made:

Now ignore that mind-map because it does you no good. It’s highly subjective and inconclusive. However, it does demonstrate how although these subfields are distinct, they end up intersecting quite a lot. At some point in their career, linguists need to use knowledge from several areas, no matter what their specialty. To not wear you out completely, I’m focusing here on the core areas of linguistics: Phonetics and phonology (PhonPhon for short2), syntax, morphology, and semantics. I will also briefly talk about Sociolinguistics and Pragmatics3.

Right, let’s do this.

Phonetics and Phonology

Let’s start with the most recognisable and fundamental component of spoken language: sounds!

The phonetics part of phonetics and phonology is kind of the natural sciences, physics and biology, of linguistics. In phonetics, we describe speech production by analysing sound waves, vocal fold vibrations and the position of the anatomical elements of the mouth and throat. We use cool latinate terms, like alveolar and labiodental, to formally describe sounds, like voiced alveolar fricative (= the sound /z/ in zoo). The known possible sounds speakers can produce in the languages of the world are described by the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), which Rebekah will tell you all about next week4.

The phonology part of phonetics and phonology concerns itself with how these phonetic sounds organise into systems and how they’re used in languages. In a way, phonetics gives the material for phonology to build a language’s sound rule system. Phonology figures out, for example, what sounds can go together and what syllables are possible. All humans with a well-functioning vocal apparatus are able to produce the same sounds, yet different languages have different sound inventories; for example, English has a sound /θ/, the sound spelled <th> as in thing, while Swedish does not. Phonology maps these inventories and explains the rules and mechanisms behind them, looking both within one language and comparatively between languages.

Speaking of Rebekah, she summarised the difference between Phonetics and Phonology far more eloquently than I could so I’ll quote her: “Phonetics is the concrete, physical manifestation of speech sounds, and phonology is kind of the abstract side of it, how we conceptualize and store those sounds in our mind.”

Syntax (and morphology, you can come too)

Begin where I are doing to syntax explained?

Why this madness!, you may exclaim, post reading the above sentence. That, friends, is what it looks like to break syntax rules; the sentence above has a weird word order and the wrong inflections on the verbs. The same sentence obeying the rules would be: Where do I begin to explain syntax?

Syntax is one of my favourite things in the world, up there with cats and OLW Cheez Doodles. The syntax of a language is the rule system which organises word-like elements into clause structures based on the grammatical information that comes with each element. In plain English: Syntax creates sentences that look and sound right to us. This doesn’t only affect word order, but also agreement patterns (syntax rules make sure we say I sing, she sings and not I sings, she sing), and how we express semantic roles5. Syntax is kind of like the maths of linguistics; it involves a lot of problem solving and neat solutions with the aim of being as universal and objective as possible. The rules of syntax are not sensitive to prescriptive norms – the syntax of a language is a product of the language people actually produce and not what they should produce.

Morphology is, roughly, the study of word-formation. Morphology takes the smallest units of meaningful information (morphemes), puts them together if necessary, and gives them to syntax so that syntax can do its thing (much like how phonetics provides material for phonology, morphology provides material for syntax). A morpheme can be an independent word, like the preposition in, but it can also be the -ed at the end of waited, telling us that the event happened in the past. This is contrasting phonology, which deals with units which are not necessarily informative; the ‘ed’ in Edinburgh is a phonological unit, a syllable, but it gives us no grammatical information and is therefore not a morpheme. Languages can have very different types of morphological systems. English tends to separate informative units into multiple words, whereas languages like Swahili can express whole sentences in one word. Riccardo will discuss this in more detail in a few weeks.

Semantics (with a pinch of pragmatics)

Semantics is the study of meaning (she said, vaguely). When phonetics and phonology has taken care of the sounds and morphology and syntax have created phrases and sentences from those sounds, semantics takes over to make sense of it all – what does a word mean and what does a sentence mean and how does that interact with and/or influence the way we think? Let’s attempt an elevator pitch for semantics: Semantics discusses the relationship between words, phrases and sentences, and the meanings they denote; it concerns itself with the relationship between linguistic elements and the world in which they exist. (Have you got a headache yet?).

If phonetics is the physics/biology of linguistics and syntax is the maths, Semantics is the philosophy of linguistics, both theoretical and formal. In my three years of studying semantics, we went from discussing whether a sentence like The King of France is bald is true or false (considering there is no king of France in the real world), to translating phrases and words into logical denotation ( andVP = λP[λQ[λx[P(x) ∧ Q(x)]]] ), to discussing universal patterns in linguistics where semantics and syntax meet and the different methods languages use to adhere to these patterns, for example how Mandarin counts “uncountable” nouns.

Pragmatics follows semantics in that it is also a study of meaning, but pragmatics concerns the way we interpret utterances. It is much more concerned with discourse, language in actual use and language subtexts. For example, pragmatics can describe the mechanisms involved when we interpret the sentence ‘it’s cold in here’ to mean ‘can you close the window?’.

Sociolinguistics and historical linguistics

Sociolinguistics has given me about 80% of my worthy dinner table conversations about linguistics. It is the study of the way language interacts with society, identity, communities and other social aspects of our world, and it also includes the study of geographical dialects (dialectology). Sociolinguistics is essentially the study of language variation and change within the above areas, both at a specific point in time (synchronically) and across a period of time (diachronically); my post last week, as well as Riccardo’s and Sabina’s posts in the weeks before, dealt with issues relevant for sociolinguistics.

When studying the HLC’s speciality historical linguistics, which involves the historical variation and change of language(s), we often need to consider sociolinguistics as a factor in why a certain historical language change has taken place or why we see a variation in the linguistic phenomenon we’re investigating. We also often need to consider several other fields of linguistics in order to understand a phenomenon, which can play out something like this:

- Is this strange spelling variation found in this 16th century letter because it was pronounced differently (phonetics, phonology), and if so, was it because of a dialectal difference (sociolinguistics)? Or, does this spelling actually indicate a different function of the word (morphology, semantics)?

- What caused this strange word order change starting in the 14th century? Did it start within the syntax itself, triggered by an earlier different change, or did it arise from a method of trying to focus the reader’s attention on something specific in the clause (information structure, pragmatics)? Did that word order arise because this language was in contact with speakers of another language which had that word order (sociolinguistics, typology)?

To summarise, phonetics and phonology gives us sounds and organises them. The sounds become morphemes which are put into the syntax. The syntactic output is then interpreted through semantics and pragmatics. Finally, the external context in which this all takes place and is interpreted is dealt with by sociolinguistics. Makes sense?

There is so much more to say about each of these subfields; it’s hard to do any of them justice in such a brief format! However, the point of this post was to give you a foundation to stand on when we go into these topics more in-depth in the future. If you have any questions or anything you’d like to know more about, you can always comment or email, or have a look at some of the literature I mention in the footnotes. Next week, Rebekah will give us some background on the IPA – one of the most important tools for any linguist. Thanks for reading!

Footnotes

1I had to bring out the whole arsenal of introductory textbooks to use as inspiration for this post. Titles include but are not limited to: Beginning Linguistics by Laurie Bauer; A Practical introduction to Phonetics by J.C. Catford; A Historical Syntax of English by Bettelou Los; What is Morphology? By Mark Aronoff and Kristen Fudeman; Meaning: A slim guide to Semantics by Paul Elborne; Pragmatics by Yan Huang; and Introducing Sociolinguistics by Miriam Meyerhoff. I also consulted old lecture notes from my undergraduate studies at the University of York.

2This is of course not an official term, just a nickname used by students.

3We’ll hopefully get back to some of the others another time. For now, if you are interested, a description of most of the subfields is available from a quick google search of each of the names you find in the mind map.

4If you want a sneak peek, you can play around with this interactive IPA chart where clicking a sound on the chart will give you its pronunciation.

5This is more visible in languages that have an active case system. English has lost case on all proper nouns, but we can still see the remains of the English case system on pronouns (he–him–his).

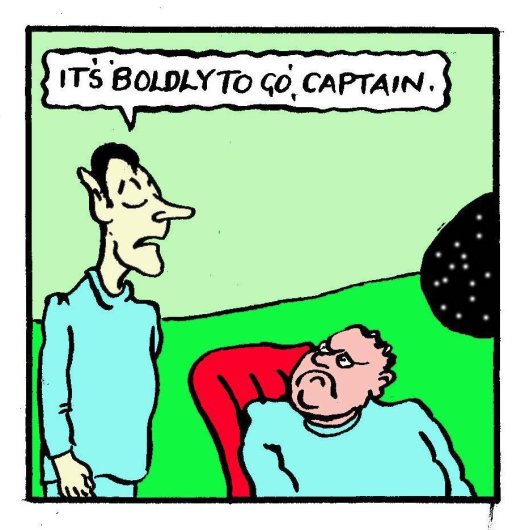

Or rather, “To go boldly”1

Or rather, “To go boldly”1