Having looked at the dialects of Old English, Middle English, and Modern English, let’s return to Old English again!

Today, let’s look at morphology.

But first, what is morphology, really?

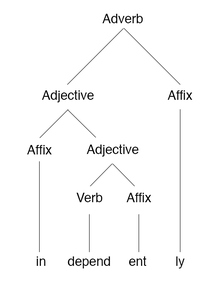

Well, in linguistics, morphology is the study of words. Specifically, morphological studies look at how words are formed and analyse a word’s structure – studying, for example, stems, root words, prefixes, and suffixes.

This may mean that you separate a word into its different morphemes to study how a word is constructed. Here is an example of how that might look, based on the word independently:

Got it? Great! Let’s move on to Old English morphology!

Now, when it comes to morphology, Old English is quite different from Modern English.

Being much closer in nature to Proto-Germanic than modern English is, Old English has a morphological system that is quite similar to its predecessor. If you want to have a modern language to compare with, Old English morphology might actually be closer to the system used in modern Icelandic than it is to modern English! (If you are unfamiliar with Icelandic, think a more conservative version of modern German).

What does that mean, though?

First, it means that Old English had retained five grammatical cases:

- Nominative

- Accusative

- Genitive

- Dative

- (Instrumental)

(The instrumental case is quite rare in Old English, so you could say that it really only retained four).

Three grammatical genders in nouns:

- Masculine

- Feminine

- Neuter

And two grammatical numbers:

- Singular

- Plural

In addition, Old English had dual pronouns, meaning pronouns that referred to, specifically, two people – no more, no less.

As you can probably see, this is quite different from what Modern English does.

If you can’t quite put your finger at exactly what is different…

- Modern English has retained the nominative, accusative and genitive case, but only in pronouns. So, we find differences in I/he (nominative), me/him (accusative), and mine/his (genitive), but not really anywhere else. In Old English, though, we would find a specific inflection following the nouns, verbs, etc. for this too (so a word like se cyning ‘the king’ in the nominative form becomes þæs cyninges ‘the king’s’ in the genitive and þǣm cyninge in the dative becomes ‘for/to the king’.

- English has not retained the grammatical genders (thank any almighty power that might be listening). This means that, unlike in German, there is no declension depending on whether the word is masculine, feminine or neuter (like the infamous German articles die, der, das).

- But, as I am sure you are already well aware, English has retained its grammatical numbers (singular and plural), though it has lost the dual function that Old English had.

A bit different, clearly.

To add to the above, Old English also separated between its verbs: all verbs were divided into the categories strong or weak.

Strong verbs formed the past tense by changing a vowel – like in sing, sang, sung, while weak verbs formed it by adding an ending – like walk – walked. As you can see, Modern English has retained some of this division though we nowadays call strong verbs that have retained this feature irregular verbs while weak verbs, interestingly, are referred to as regular verbs.

Sounds easy, right? Yeah, we’re not done.

In Old English, you see, the strong verbs were divided into seven (!) different classes, each depending on how the verb’s stem changed to show past tense. I will not go through them all here – it is simply a bit too much for this blog, but check out my sources if you want to know more.

Point is, that means that there were seven different ways a verb could change to indicate past tense + the weak verbs.

Now, the weak verbs also had classes. Three, to be specific. I won’t go through those either (trust me, it’s for your benefit because you’d be stuck here all day).

So, we have two main categories and ten sub-categories.

Woof.

That’s a lot to keep track of.

And that is not even considering the changing patterns of nouns, adjectives, pronouns, etc., etc., or the numbers, or context.

Gosh, and I keep getting stuck at concord in Modern English! (Swedish doesn’t use something equivalent to the s on verbs in third-person singular, and it is one of my more commonly made mistakes when writing in English).

Old English morphology is obviously very different from Modern English! And, although this is obviously just a very brief glance, I’m going to stop there. This is the very broad strokes of some of the major differences between Old English and Modern English, but we’ll explore more how it went from this:

Se cyning het hie feohtan ongean Peohtas

Extract from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, anno 449

to this:

The king commanded them to fight against [the] Picts

Translation of the extract from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, anno 449

next week, when we take a look at the changing system of Middle English morphology and experience the loss of many of the inherited morphological systems! Join me then!

.

References

For this post, I’ve relied on my own previous studies of Old English Grammar by Alistair Campbell (1959); An introduction to Old English by Richard M. Hogg (2002) and Old English: A historical linguistic companion by Roger Lass (1994).

However, I’ll admit to having refreshed my knowledge of Old English morphology by having a look at Wikipedia, as well as comparing it with modern English morphology in the same place.

The text from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, both in Old English and in Modern, is retrieved from here.