Okay, so the plan was to continue with Old English syntax today. Then I started writing and realised that there were so many things that I should explain before looking closer at Old English syntax.

So, today, we’re doing a syntactic primer!

I’ll use this post to introduce you to the topic of syntax, which is basically the order of words and phrases used to create a well-formed sentence in any given language.

By doing so, I hope that you’ll be prepared for next week when we’ll look at Old English syntax!

Okay, let’s get started.

There are many kinds of word-order arrangements. In modern English, you use SVO-order in your sentences, meaning that you put your subject first, your verb next and last your object. So, for example, “I like you“. Simple enough. This is a very common structure (estimated to be used by approximately one-third of the world’s current languages).

Ever seen Star Wars? Even if you haven’t, you probably know that Yoda tends to use a different kind of order to structure his sentences. This order is usually showing a preference for OSV – meaning that the object comes first, then the subject, and lastly, the verb: You I like. Unlike SVO, this is a very uncommon structure and is actually the rarest of all word orders by a significant margin. In a recent study by Hammarström (2016), in which 5252 languages were studied, only 0,3% had OSV-order, while 40,3% had SVO.

There are others too :

| Order | Example | Example of language | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subject-object-verb | I you like | Japanese | |

| Verb-subject-object | Like I you | Classic Arabic | |

| Verb-object-subject | Like you I | Malagasy | |

| Object-verb-subject | You like I | Hixkaryana |

Alright, so we’ve done a very basic overview of different word orders. There are two more things that we have to talk about: V2 and VF.

That is, Verb second and Verb final.

V2 is quite common in Germanic languages and works like this: a finite verb of a clause or sentence is placed in second position, with one single constituent preceding it. This constituent functions as the clause topic.

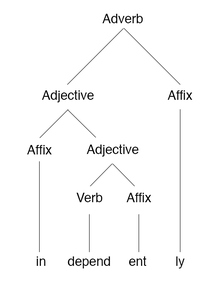

Please note that this does not necessarily mean that there is only one word preceding the verb, but one constituent (that is, a word or a group of words that function as a unit in a hierarchical structure). Anyway, V2 is still alive and well in many Germanic languages, for example in my native Swedish:

- Jag vet inte. I do not know

- Inte vet jag. Do not know I

Yeah, I know, the second example becomes extremely awkward in English but works just fine in Swedish1 . The point is, the verb vet (know) here does not change position, even though everything else does. Clearly, as you can see, that doesn’t work very well in English.

But it used to!

I just won’t tell you about how until next week.

Because we still have one more thing to deal with: VF.

Honestly, this pretty much means what you would expect it to: the verbs in a verb-final language almost always fall in final position. In German, for example, we see this happening in embedded clauses that follow a complementiser:

dass du so klug bist

that you so smart are

“that you are so smart”

Again, awkward in English.

But, again, it didn’t use to be! But we’ll get back to that too.

So, you know that Yoda’s language might not be all that odd (though rare)2 , that modern English generally use SVO word order3 , and that this wasn’t always the case.

I think that that is enough for us to dig into Old English next week. And, so, I leave you to mull things over until then. As always, if you want to know more, check out my references!

.

References

Harald Hammarström. 2016. Linguistic diversity and language evolution. Journal of Language Evolution. 1: 1. pp. 19-29. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/jole/lzw002

Adrienne Lafrance. 2015. An unusual way of speaking, Yoda has. Hmmm? The Atlantic. Find it here.

Geoffrey K. Pullum. 2018. Yoda’s syntax the Tribune analyzes; supply more details I will! Language Log. Find it here.

Beatrice Santorini & Anthony Kroch. 2007-. The syntax of natural language: An online introduction using the Trees program. Find it here. (I’ve primarily looked at Chapter 14 for this post).

Wikipedia. V2 word order. Find it here.

Wikipedia. Word order. Find it here.

If you’d like a more comprehensive primer to syntax, I personally like:

Andrew Carnie. 2013. Syntax: A generative introduction. 2nd ed. Malden; Oxford; Victoria: Blackwell Publishin Ltd.

Jim Miller. 2008. Introduction to English syntax. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Or rather, “To go boldly”1

Or rather, “To go boldly”1